Psychology

Are Animals Conscious?

The Enlightenment failed to frame the proper relations of matter and mind.

Posted December 22, 2020

The Unified Theory of Knowledge argues that the Enlightenment failed to generate a consilient system of understanding that enabled us to make sense of the human condition, the world, and our knowledge of both. This failure is seen most obviously in the Enlightenment Gap, which refers to the failure of modernist philosophy (from Hume to Kant) and natural science (Galileo into Newton) to generate the clear and proper understanding of the relationship between matter and mind and scientific and social knowledge. The problem of psychology is the downstream consequence of the Enlightenment Gap, and the Unified Theory affords us a way to solve the problem and to engender a system that allows for the relations of matter and mind and science and social knowledge to be properly understood.

It follows from the Enlightenment Gap that we should see profound confusions regarding the nature of animal consciousness. This indeed is the case. Consider, for example, that during my education, the scholars Rene Descartes and George Romanes have been repeatedly characterized as taking diametrically opposing views on animal consciousness. It is often claimed that Descartes thought that only humans were conscious and that all other animals were automata. We can see this in many writings. Drawing on Descartes’ analysis, in 1689 Malebranche wrote (translated from Huxley, 1896):

In dogs, cats, and other animals, there is neither intelligence nor a spiritual soul in the usual sense. They eat without pleasure; they cry without pain; they believe without knowing it; they desire nothing; they know nothing; and if they act in what seems to be an intelligent and purposive manner, it is only because God has made them fit to survive, and has constructed their bodies in such a way that they can organically avoid—without knowing that they do so—everything that might destroy them and that they seem to fear.

In contrast to Descartes, George Romanes argued that many animals had a rich mental life. A close friend of Darwin's, he was one of the founders of comparative psychology and wrote books on animal intelligence and the mental lives of animals.

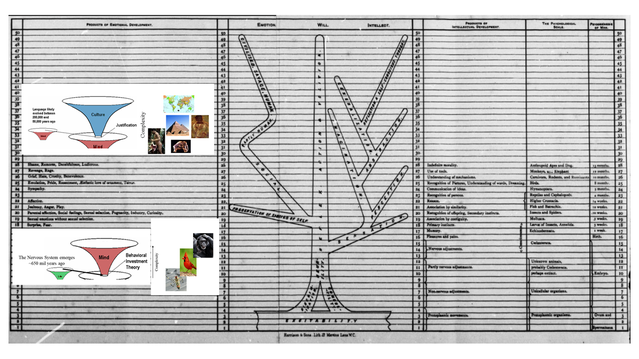

He opened his book, Mental Evolution in Animals, by breaking up mental capacities into 50 different levels of intellectual, emotional, and conscious development. Modern adult humans, with their capacity for language, culture, and explicit self-reflection occupied the top rungs. The "highest" animals, such as the apes, appeared at rung 28, which he characterized by having an “indefinite morality” and the capacity to experience remorse, shame, deceit, and the ludicrous. Birds occupied level 25, which could understand words and pictures and experience terror. Just beneath them were bees and ants, which could communicate ideas and feel sympathy. Several steps down (at level 18) were worms and insect larvae, which experienced primary instincts and the emotions of surprise and fear.

At first blush, it appears that Romanes and Darwin do indeed advocate for radically different views concerning animal consciousness. And it is the case that there is a real difference of opinion between them. However, much of the confusion stems from the failure of the Enlightenment to produce an effective language game concerning what is meant by “consciousness,” and this hides the fact that there was much greater overlap between them than first appearances suggest.

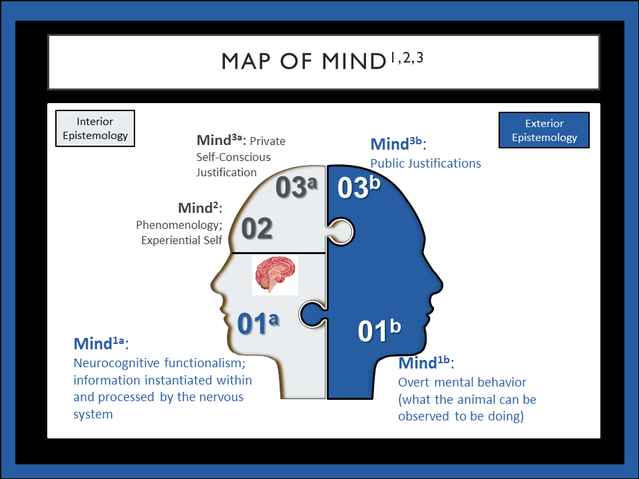

Thankfully, with the ToK System and Map of Mind1,2,3 provided by the Unified Theory, we are in a much better position to make sense of the terrain. We can start with Romanes and note that his concept of “mental evolution” corresponds directly with the ToK System and the Mind dimension of behavioral complexity. For both Romanes and the ToK System, “mental” is properly considered to be an adjective that corresponds to the complex adaptive plane of existence inhabited by animals with brains.

Also consistent with the Map of Mind1,2,3, Romanes has many levels of mental behaviors — 15 to be precise--that precede the emergence of conscious experience, which he asserts to be pleasure and pain (an assertion I think is likely correct). That is, there are many layers of neurocognitive reflexive and action control procedural systems that almost certainly involve nothing akin to what we mean when we say something is conscious or has conscious experiences (i.e., the domain of Mind1). This raises the question of what consciousness means for Romanes. Placed in the language of the Map of Mind1,2,3, we can see that Romanes thought of consciousness in terms of what modern scholars call sentience, which refers to the capacity to have any form of subjective inner experience. On the Map of Mind1,2,3, this is the transition from Mind1 into Mind2.

Also consistent with the ToK System, Romanes makes a significant and qualitative distinction between animals and humans. Almost the entire upper half of Romanes’ levels of mental evolution are occupied only by humans. Self-conscious reflection (i.e., Mind3 on the Map of Mind) starts at level 34 and proceeds for 16 more levels. In other words, as far as animal mental evolution, for Romanes it was all about the space between Mind1 and Mind2.

This figure depicts Romanes 50 levels, and has the Mind and Culture dimensions placed on it. The diagram is from the beginning of Romanes book, which is available here. This demonstrates that there is a broad alignment between Romanes levels and the Mind and Culture dimensions on the ToK System. (Please note that there are many differences in the specifics; see here for a modern view of animal consciousness and its various dimensions that is more consistent with the Unified Theory).

Let us now return to Descartes, and consider his famous dictum for consciousness that for him justified why mind and matter needed to be divided into separate worlds: “I think, therefore I am.” This is a crystal clear example of Mind3. Indeed, as was covered by John Vervaeke in the Untangling the World Knot of Consciousness series, Descartes thought about consciousness in terms of how perceptions and feelings become ready for reason. In other words, for Descartes, consciousness was found in the jump from Mind2 into Mind3 and the feedback between them. Thus, in this language game, the conclusion is that there is no (self-reflective) consciousness for animals.

But this is exactly Romanes conclusion as well! Self-conscious reflection starts at level 34; several levels above the "highest" nonhuman animals. Thus, there is strong agreement here between Romanes and Descartes. The difference is that, for Romanes, consciousness refers to the jump from Mind1 to Mind2. In contrast, for Descartes, consciousness refers to the transition from and feedback between Mind2 to Mind3. Placed on the Map of Mind1,2,3, we can now see that it is primarily the language game and what “consciousness” refers to in the world that is different. If they both had the proper map of mind, much confusion and pointless debates could have been avoided (and, perhaps, much more moral treatment of sentient animals).

But what about the frequent claim, as expressed in the prior quote by Malebranche, that Descartes’ model suggests that animals experience no pleasure or pain? A careful reading of the quotation from Malebranche shows he adds the qualifier “in the usual sense”; that is, in the human self-reflective, self-aware sense. And the passage shows that Malebranche is emphasizing that, although they seem to have purpose, intelligence, and experience fear, the claim is that they are this way but “without knowing that they do so.” Here again, we see that the qualifier points to Mind3 reflective knowing as being a central ingredient to what is being emphasized by Malebranche. [Note, as the 2012 Cambridge Declaration of Animal Consciousness makes clear, Malebranche is completely wrong in this set of claims. And, in light of modern knowledge, they can be considered essentially immoral; I am simply dissecting his justifications to show his thinking].

The conclusion is bolstered by two points. First, in the early part of the 17th Century, Descartes had a very limited understanding for adequately framing how the brain and nervous system work as an integrated information processor; thus, there was much confusion about the ontology of the mental. Second, Descartes clearly acknowledged sensations and perceptions existed. He generally considered them bodily experiences that were understandable from a mechanical perspective. Thus, it is not clear at all that Descartes would have said that animals do not experience the sensations of pleasure or pain. Rather, his primary conclusion was that they could not reflect on their meaning, and thus suffer in the same way. In short, it is very possible that he considered animals as having a Mind2. This is how the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy puts it:

Although [Descartes] conception of animals treated them as reflex-driven machines, with no intellectual capacities, it is important to recognize that he took mechanistic explanation to be perfectly adequate for explaining sensation and perception — aspects of animal behavior that are nowadays often associated with consciousness. He drew the line only at rational thought and understanding.

The bottom-line conclusion is unmistakable. The Enlightenment failed to produce a clear map of mind and consciousness, and our grammar of understanding has been confused ever since. So profound is the confusion that the entire discipline of scientific psychology is mired in equivocation about behavior, mental processes, and consciousness. It is time for an Enlightenment reboot with the proper relations between matter and mind and philosophical framework for a scientific psychology. The Unified Theory of Knowledge shines the light on the path forward on how this is accomplished.